This book about the first woman doctor in America contains fascinating details about the Blackwell sisters, their struggles, and the times they lived in. Elizabeth Blackwell is to be commended for her accomplishments, but it appears that she was not a nice person.

This is a review of the book The Doctors Blackwell: How Two Pioneering Sisters Brought Medicine to Women – and Women to Medicine, by Janice P. Nimura. The book was a New York Times bestseller and was praised as meticulously researched, drawing from family letters and diaries.

In 1950, only 6% of the doctors in America were women. Today about half of all medical students are female and more than 30% of American doctors are women. When Elizabeth Blackwell was born, it was impossible for a woman to become a doctor. The very idea was unthinkable, and no woman had ever been admitted to a medical school. Elizabeth and her sister Emily were heroically tenacious in fighting the medical establishment and they triumphed in the end. Elizabeth was the first woman in America to earn a medical degree, and her sister soon followed. I thought I owed them a debt of gratitude. Their pioneering efforts helped make it easier for me to earn an MD degree in 1970. There was still prejudice, as I recounted in my book Women Aren’t Supposed to Fly: The Memoirs of a Female Flight Surgeon.

According to Nimura,

…at the age of 24, Elizabeth Blackwell had selected medicine as a means of proving a truth she believed to be divinely sanctioned: that women could be anything they wished according to the limits of individual talent and toil, and in reaching their fullest potential would raise humanity closer to its ideal.

This despite the fact that Blackwell confessed that “the very thought of dwelling on the structure of the human body and its ailments filled me with disgust”.

“Women shouldn’t be doctors”

Nimura reports some of the many objections that were raised:

- Women didn’t have the intellectual and physical endurance that were required

- No female would be welcome among male medical students

- No self-respecting woman would voluntarily expose herself to the naked realities of the body in the company of men

- Menstruation incapacitated women every month.

The state of medicine

In 1849, when Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in America to receive an MD, medicine was in a parlous state. Conventional doctors did more harm than good. Bloodletting was a standard treatment, and everything was on offer: mesmerism, phrenology, the water cure, etc. There were various schools of thought, such as eclecticism. The germ theory of disease and the idea of randomized controlled clinical trials were far in the future. It wasn’t until 1910 that the Flexner Report advocated standardizing medical education and putting it on a scientific basis.

Nimura describes in detail the struggles of Blackwell to gain admission to a medical school. These schools offered an education that sounds pretty sketchy to me. They had a term of 16 weeks. To get a diploma, students were required to attend the identical course of lectures in two successive years and to study on their own with “respectable” practitioners. She was eventually admitted to Geneva Medical College after the students were allowed to vote. Apparently, they took it as a great joke and an opportunity to make mischief: they voted unanimously to admit her. Nimura says their decision horrified the faculty, but the deed was done.

According to Nimura, other women were not supportive: they thought Blackwell must be either wicked or insane. A woman in France was quoted as saying, “Oh, it is too horrid! I’m sure I could never touch her hand! Only to think that those long fingers of hers had been cutting up people.”

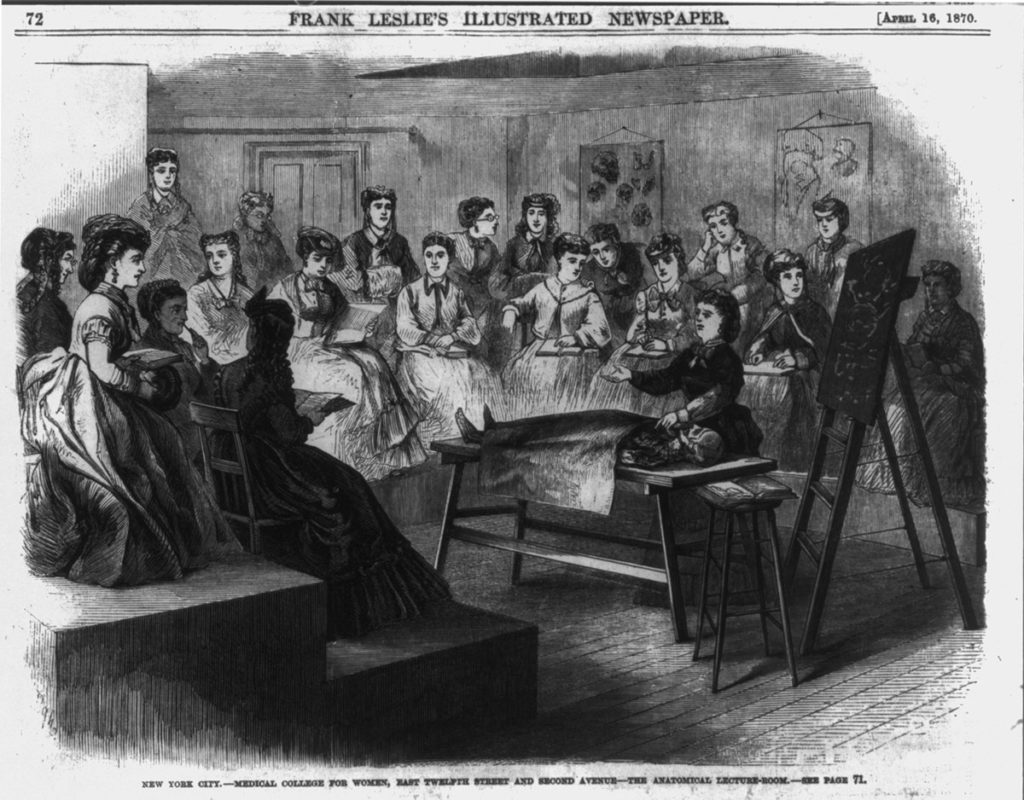

Nimura says Emily was actually the better doctor and became an accomplished surgeon. Elizabeth preferred writing and lecturing on raising healthy children. She worked hard to promote women in medicine, but she found dealing with actual patients repulsive. Together, they founded the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children, an institution that outlived them and only closed in 1981. They established the Woman’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary, offering an unprecedented three years of study. Among many other accomplishments, Elizabeth was the first woman to be listed on the British Medical Register.

Library of Congress newspaper image of the anatomy lecture room at the Woman’s Medical College of New York Infirmary (April 16, 1870)

Fascinating details

I thoroughly enjoyed reading the book. It paints a vivid picture of her family, her background, and the times, including the effects of the Civil War and a mob attack on their Infirmary for “killing women in childbirth with cold water”, and introduces characters like Florence Nightingale, Lady Byron, and Fanny Kemble, who is quoted as saying “Trust a woman – as a Doctor! – NEVER!” Elizabeth even met President Lincoln.

I was intrigued to learn that Elizabeth had a prosthetic eye. She sought additional training in England and France. When treating an infant with ophthalmia of the newborn during a period of training at La Maternité in Paris, a drop of contaminated liquid splashed into her eye. After a long and painful illness and many trials of useless treatments, she eventually lost her left eye. How sad! It could easily have been cured by antibiotics, but they hadn’t been discovered yet.

Not a nice person

She was scornful of the very women she wanted to inspire. She blamed the poor state of women on the women themselves. She is quoted as saying,

I feel neither love nor pity for men, for individuals – they may starve, cut each other’s throats or perform any other gentle diversion suitable to the age – without any attempt to stop them on my part, for their own sakes. But I have boundless love and faith in Man, and will work for the race day and night.

That may be admirably honest, but it does not strike me as sympathetic or endearing.

I would not have liked to meet her. Nimura describes her as prickly, stubborn, difficult, and opinionated. And she did things I can’t approve of. She selected an orphan from the New York Almshouse and raised her to be her servant and acolyte. “Kitty” was expected to eschew a career of her own and to follow her mentor’s example by never marrying. Blackwell didn’t support the women’s rights movement. She opposed vaccination, dabbled in spiritualism, and experimented with treatments that we know today to be ineffective.

The sisters died within months of each other in 1910, the year the Flexner Report came out.

Conclusion: An important contribution to the history of medicine

I can recommend this book, although I can’t recommend everything the Blackwell sisters did. We live in a very different world today, a world that has gone far beyond the Blackwells’ accomplishments and fulfilled their goal of making medical education available to all. Thank you, Elizabeth and Emily, for your heroic perseverance, and thank you, Janice Nimura, for writing an excellent book.

This article was originally published in the Science-Based Medicine Blog.