New study in The New England Journal of Medicine finds impressive evidence that weekly semaglutide injections produce clinically significant weight loss as well as many other benefits, approaching the improvements seen with weight loss surgery. Not a definitive answer to obesity, but a very encouraging step in the right direction. Science works.

Science works. The rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines is a case in point. Wouldn’t it be great if science found a safe and effective way for obese people to lose weight? We can hope, and we will have to wait for good evidence; but meanwhile, a new study in The New England Journal of Medicine is an encouraging sign that science is working on the problem and may eventually find a solution. “Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity” by Wilding et al. was published on March 18, 2021.

Previously available treatments

Obesity is a recognized health risk, but efforts to reverse obesity have been problematic. Diets and exercise work in the short term, but long-lasting weight loss is seldom achieved. Weight-loss surgery works but is drastic, risky, and requires lifelong nutritional supplementation.

There are various medications on the market. They are mostly prescription only, but sometimes available at a lower dose as over-the-counter meds (e.g. Alli). The use of medications has been limited by modest efficacy, safety concerns, and cost. A convenient table can be found here. Some highlights: orlistat (sold over-the-counter as Alli) causes diarrhea, gas, stomach pain, and leakage of oily stools, and rare cases of severe liver injury have been reported. Lorcaserin was withdrawn from the market in 2020 because of evidence that it increased the occurrence of cancers. Phentermine-topiramate (Osymia) has multiple side effects and may cause birth defects; there are many contraindications such as glaucoma or hyperthyroidism. Naltrexone-bupropion (Contrave) has a long list of side effects and contraindications and may increase the risk of suicide. Liraglutide (Saxenda) may increase the chance of developing pancreatitis.

The fen-phen disaster was a cautionary tale. It was a very popular weight loss drug until it was found to cause heart valve disease and pulmonary hypertension and was withdrawn from the market. There were over $13 billion in legal damages.

Innumerable dietary supplements are advertised to help people lose weight, but they are mostly untested or inadequately tested. When they do work, it’s usually because they contain unapproved stimulants like amphetamine analogues or ephedra.

The new study

Semaglutide is a treatment for diabetes. It comes in two forms: an oral 3mg tablet (Rybelsus) taken daily and a 0.25 mg subcutaneous injection (Ozempic) given once a week. Serendipity struck when clinicians discovered that people taking semaglutide lost weight, and they thought of repurposing it as a weight loss drug. After a phase 2 trial confirmed that it caused weight loss in type 2 diabetics and overweight adults, this new trial was designed to test the safety and efficacy of injecting 2.4mg once weekly.

It was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial carried out at 129 sites in 16 countries in Asia, Europe, North America, and South America. Participants were 18 years of age or older who had one or more unsuccessful dietary efforts to lose weight and either a BMI of 30 or greater or a BMI of 27 or greater with one or more treated or untreated weight-related coexisting conditions. Diabetics were not eligible, nor were those who had had weight loss surgery or pancreatitis or had recently taken antiobesity medications.

Semaglutide was administered by prefilled pen injectors starting with 0.25 mg and gradually increasing to 2.4 mg. There were a total of 1,961 participants, 1,306 randomly assigned to receive semaglutide and 655 assigned to receive placebo. Most participants were female (74.1%) and white (75.1%). Mean age 46, mean body weight 105.3, mean BMI 37.9. 43.7% had prediabetes. In addition to the injections, all participants received individual counselling sessions every four weeks to help them adhere to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity. The study lasted 68 weeks.

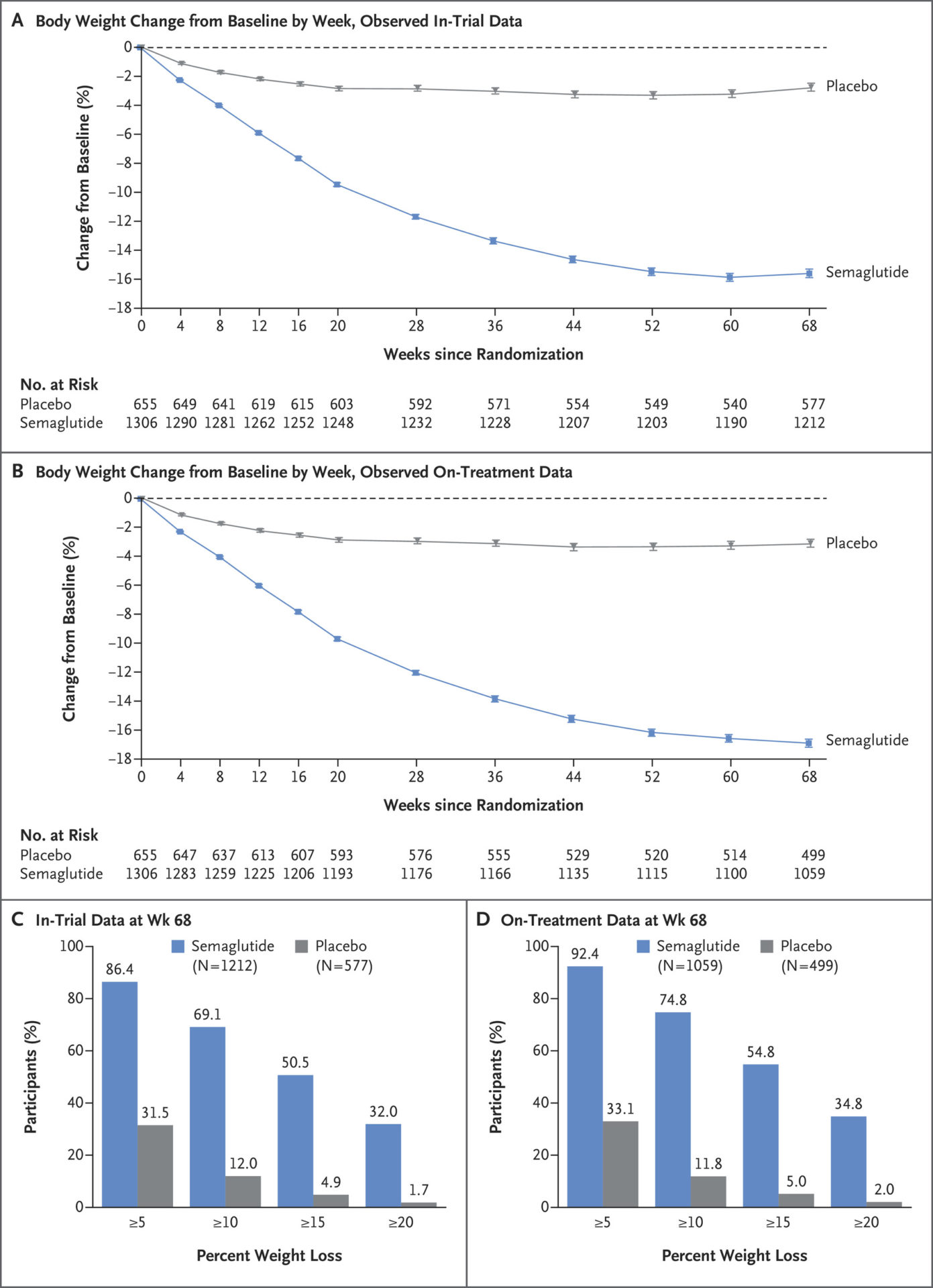

The results were dramatic. Body weight dropped by 14.9% with semaglutide compared to 2.4% with placebo. 86.4% of participants lost 5% or more of body weight with semaglutide compared to 31.5% with placebo. 69.1% of the semaglutide group lost 10% or more, compared to 12.0% of the placebo group. Semaglutide clearly produced clinically significant weight loss.

Concerns

Adverse events were more common in the semaglutide group (74.2% vs. 47.9%). Nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and constipation were reported, but these were typically mild-to-moderate, transient, and resolved without discontinuing the regimen. Serious adverse events were reported in 9.8% of the semaglutide group and 6.4% of the placebo group. 7.0% of the semaglutide group and 3.1% of the placebo group discontinued treatment due to gastrointestinal events. Gallbladder-related disorders were reported in 2.6% of the semaglutide group vs. 3.1% of the placebo group.

Other benefits

In addition to weight loss, patients taking semaglutide had greater reductions in waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, C-reactive protein, and fasting lipid levels. 84.1% of participants who had prediabetes reverted to normoglycemia with semaglutide, compared to 47.8% with placebo. Physical functioning also improved. There was a reduction in calorie intake due to decreased appetite. The benefits of semaglutide for weight and prediabetes approached the benefits seen in weight loss surgery.

Conclusion: a promising first step

This study is encouraging but far from definitive. An accompanying editorial characterized it as “a good beginning” but called for further studies, to include a comparison with weight loss surgery. There are no easy answers, but it’s good to know that scientists are working on the problem and making progress. I urge you to look at the detailed, careful evidence provided here and compare that to the lack of evidence or poor excuse for evidence for a typical CAM weight loss product. There’s no comparison.

This article was originally published in the Science-Based Medicine Blog.